A sustainably-minded renovation

how we approached decorating our childrens’ bedrooms the eco friendly way

(long read)

When my daughter was born almost eight years ago, she spent seven days in the NICU with suspected meningitis. There were tests and doctors and midwives and an unsurety that stuck for a long time, alongside how precious it is to be the guardian of a life. It left its mark. Why wouldn’t we do all we could to protect it? To this day, that experience shaped and guided our journey as parents, helping my husband and I identify our values and define what is truly important to us. A green home is one of those priorities.

We didn't get the keys to our new house in the English countryside until a dark November night and the first thing to hit us as we stepped over the threshold was - the smell. Damp. Damp and cold and mildew and sealed up rooms and cat-shredded carpets. I could have cried on the spot in what was to become our childrens’ bedrooms, the hidden problems revealed for the first time. This was far from the safe, sustainable home we envisioned. But we had something in our arsenal - my husband and I had already done this once before.

Renovating our previous home took a long time, but we made it something beautiful. During that process we learnt a lot about renovation, DIY and the options available for greener, more environmentally friendly decorating. From wallpapers without PVC (plastic) to paints excluding acrylics (more plastic), we took what we already knew and expanded our research further. Here I share with you what we learnt with the first two rooms we renovated in our new house in rural Oxfordshire - our daughter and son’s bedrooms.

Decorating for longevity: creating a sustainable home

Our daughter (7) and son (4) each have their own bedrooms and our first task was to make them feel like home for them. This meant taking into account their individual passions, but being sensitive to their futures and decorating with longevity in mind. No fads. Decorating for children without succumbing to their demands can be a challenge, especially when children love something immensely and heartbreakingly passionately - for about three months at a time. Everyone will have a budget or limitations on their time and we believe our children should be exposed to this from a young age to help them define their priorities as they grow. We started by communicating openly with the children about what was going to happen, what they like and what is realistically in our capacity.

Decorating for longevity is, by its very definition, a guaranteed way to achieve a sustainable home. Of course, painted walls may need refreshing. or woodwork may require touching up over time, but redecorating regularly for the latest trends, or buying furniture every few years because it no longer ‘goes’ is the antithesis to an eco friendly home. If we buy it, more will be made, consumed, then thrown away, and the waste cycle continues to grow. Instead, use this opportunity to press pause.

Think about your future and how that may look. Create a vision board of howyou wish your home to look but more importantly, how you want your home to feel. Colour is very personal and can envoke strong emotions. Lean into this and listen to yourself first - it may help you not to be swayed by just what’s in vogue. Lastly, be mindful of the purpose a space is required for. For children, a one year old’s needs may be very different to a four year old’s, but they both require the same thing from the space they sleep in - a place for rest, relaxation and calmness. This is what we bore in mind when choosing furniture layout, paint colours and decoration for both our son’s bedroom and daughter’s bedroom. But first we had to tackle the mold.

Sustainable insulators - cork, lime and vented windows

We inherited a vinyl border in our son’s bedroom and, to my horror, I discovered it was the perfect breeding ground for black mould. Black mould is a fungus and can trigger an immune response, so it can be very dangerous. The vinyl plastic acted as a barrier, trapping moisture between it, the lining paper and the plaster and brickwork beyond. It was the evidence we needed for the theory that old houses like ours need to breathe*, not be sealed shut, unless you are able to mechanically manage airflow and moisture within a property (ie hermetically sealed or ‘Passive’ houses.). If a home cannot transpire, mould will be its constant tenant. In the UK, most of our damp proofing solutions appear to be targeted towards fighting moist getting in, and treatments are sold to essentially seal up a house - nothing in, but also, nothing out. Without also installing a Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery (MVHR) system to manage the moisture content - which is significantly more complicated to do in an old property than a new build - it appears not to be a solution at all. Us, our pets, our laundry and washing facilities all create moisture in our homes. If it can't escape, where does the water go? We took a leap of faith and went against the industry standards for damp proofing older properties. We chose to let our walls breathe.

We believe our house was built sometime around 1920 and is of single brick construction meaning there is no cavity to fill or insulate. We discovered evidence under floorboards that at some point the house had used lime plaster with horsehair interally. Lime plaster is made from naturally derived components, typically sand, water and the lime itself, which are inorganic compounds, calcium oxides and/or hydroxides. This means its make up allows for the passage of air and moisture without a barrier to stop their movement through. Gypsum plaster does not do this in the same way. Gypsum itself is a sulfate mineral. Ground down to a powder, it can then be recombined with water (dihydrate) so it becomes maleable. However, once exposed again to the air, it rapidly crystalises and returns to its original rock form making it almost impermeable once again. (Although please note, I’m no chemist.)

We discovered a concrete render had been applied over the internal brickwork for the external facing walls, used as an insulator in lieu of an insulating cavity, with gypsum plaster smoothing over the surface layer. The concrete may have insulated to a degree, but it essentially acted as a damp proofing layer, stopping the travel of any moisture. The paper hung off the walls and blooms of mould once hidden by furniture were now revealed. As the paper was removed, the gypsum plaster shot off in sheets. We removed it and the concrete render (I did this with a hammer drill myself) and gave the room a chance to breathe again.

Old, leaking windows were replaced with new units that included opening vents to assist in the movement of air and moisture around the space. The walls were then lined with a thick cork matting. Cork is the phellem layer of bark tissue, usually harvested from the cork oak (Quercus suber). It is naturally boyant and has fire retardant properties, as well as being vapour permeable - the key to improving our damp issues and home insulation. It can be harvested sustainably and from renewable sources and the cork boards we chose were free from synthetic resins and carcinogenic materials**. It was the natural insulator choice for us and allowed us some big step forwards to creating our natural, green home.

breathable Plasters and plastic free bonders

We used a cork compatible mortar to adhere the boards to the walls, one that was free from any plastic bonders to ensure the cork’s breathability properties remained. The surface was then plastered using lime, although the application left a slightly rough texture and not a glass-like finish that gyp plaster does. This may have been an application error but because we are seeking to repair lost character and age in the property, it felt right to leave it with some bumps and undulations. Be mindful, lime takes time to ‘cure’ so don’t expect to be painting your walls within a week. We didn’t mind - we want a slow, sustainable home afterall and since we had both bedrooms plastered at the same time, we simply bundled the children into our bedroom and enjoyed a big family sleepover for a little while.

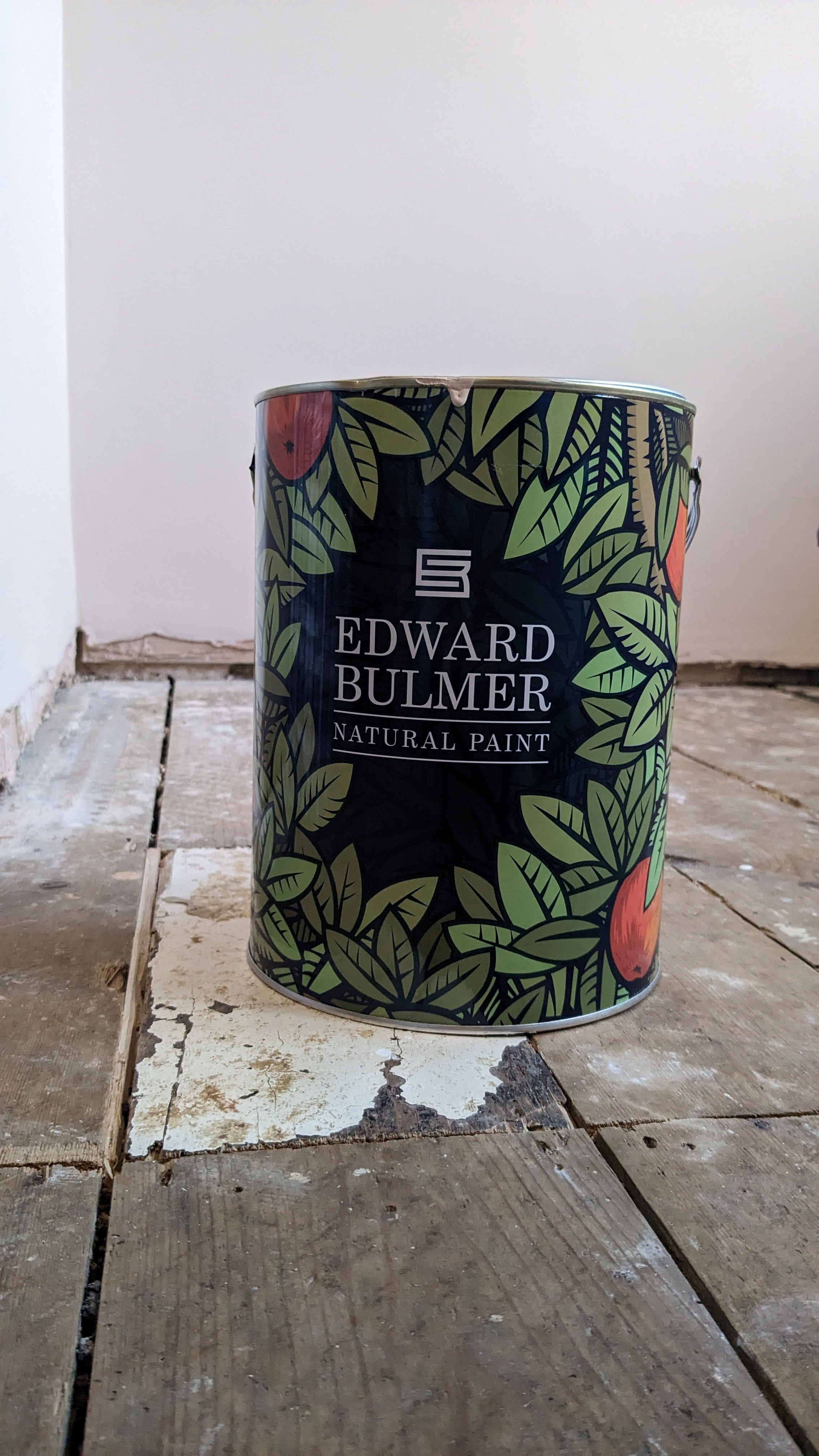

Not all eco paints are equal - the search for plastic free paints

What makes a paint environmentally-friendly? Is it the way it is packaged? It it because it’s water soluable? Is it because its pigmanets come from natural sources, or that is has low VOCs (volatile organic compounds)? These questions deserve a dedicated article in their own right. Here, I will be brief and explain what was important to me: I wanted a paint that was and came as plastic free as possible.

Formulations of paint are closely guarded industry secrets. This means it is very, very difficult to find out the chemical compounds used to make a product. However, the best way to find out more is to access the Paint Data Sheet for the product you require. For example, there are emulsions (some marketed as green, or ‘eco friendly’) which, in their data sheets include the word acrylic. Acrylic is a synthetic polymer and acrylic paints are simply polymers with pigmanets (colour) suspended within it. When the paint dries, it hardens. It is used to make a paint more durable. Vinyl paints include resins, and even waterbased emulsions can contain acrylic as a binder. Beware those marketed as sustainable - if you read the information carefully it is likely to tell you to avoid contact of the product with soil and waterways because of these plastics and other toxins, which has just made washing out your paintbrushes and rollers much more difficult. These polymers also mean paints with vinyl resin or acrylic aren’t particularly breathable - plastics trap air afterall - not in the same way natural-based paints can.

Natural paints forego acrylic binders and instead use biogenic binders, which can also significantly lower the VOC count. The smell from freshly applied paper (or paint) is called off-gassing. Off-gassing is the process where the VOCs are released into the air. As VOCs evaporate, they add to the creation of greenhouse gases which, as we know, contributes to our increased global temperatures (aka the climate crisis).

Sadly, many companies are very good at hiding whether a paint contains these polymer binders, so look carefully at the product Data Sheet or the company’s Terms and Conditions of use and, if in doubt, contact the company directly and ask the question.

Green wallpapers - sustainably produced, ethically made

By now I hope most of us are well versed in the meaning of FSC®-certification. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) operates the most rigorous certification scheme for sustainable forestry in the world*** and it was important for us to ensure the paper we chose was FSC certified. Secondly, we wanted to ensure the paper was vinyl free. Many wallpapers today are being produced with vinyl - which can, at times, be polyvinyl chloride (PVC) - as a plastic upper coating applied to the paper, typically to increase durability, longevity and to make a paper water or splash proof. Most countries hold their own regulations on what can and can not be used in a wall covering and there is little information publically on the safe usage of vinyl in wallpaper. There is evidence, however, that PVC can have added phthalates - the endochrine disrupting chemical which has been banned in toys for babies and children in some countries, including by the UK in 1999. Suffice to say, we wanted a vinyl / PVC free paper.

We tried to find a wallpaper manufactured in the UK, but failed on this occassion to find what we were looking for, for our daughter’s bedroom within our budget. Instead we found a beautiful wallpaper manufactured in Sweden by a company with strong sustainability ethics. Should you find a wallpaper you really love but aren’t sure if it’s eco friendly, check for these three things as a minimum:

1) FSC-certification. Is this paper made from sustainably managed forests? Look for the FSC logo.

2) PVC-Free Is this wallpaper free from PVC? Look for the PVC free logo.

3) VOC Content (also referred to as Emissions) VOCs for paint and wallpaper are usually rated (A+, A, B) or shown as numbers (<0.1 , <1 mg/mg3) dependent on your location and legislative requirements. The number of VOCs can also indicate whether a paper was printed using solvents or water based or plant-based inks, which have their own environmental impact.

And lastly, chose your adhesive carefully. Most sustainably-minded wallpaper manufacturers offer their own eco friendly wallpaper glues which usually contain cellulose as the adhesive, instead of resins. It’s in their favour to produce these too not only to ensure the best application for their products but also to support their sustainability credentials.

Eco friendly flooring

I despise carpet. I despise vacuuming it, cleaning up spills on it, removing stains on it, stopping it from getting shredded or flattened or any and all of the other challenges faced when you have carpet - and children (or pets). Suffice to say, carpets for the childrens’ bedrooms was not my first choice. However, its insulating properties are not to be ignored and since most of the energy lost in our homes is through heat loss, excellent insulation is essential in creating a sustainable home. For six months we lived with the old, exposed floorboards: without carpet, the rooms were very cold and very, very noisy. There’s nothing quite like the booming reverberations of a bang from upstairs to send me running in a blind panic to the childrens’ bedrooms, only to discover it was simply a dropped toy. For this reason, we decided not to install wooden floors upstairs and so I dove into the world of eco friendly carpets and underlays.

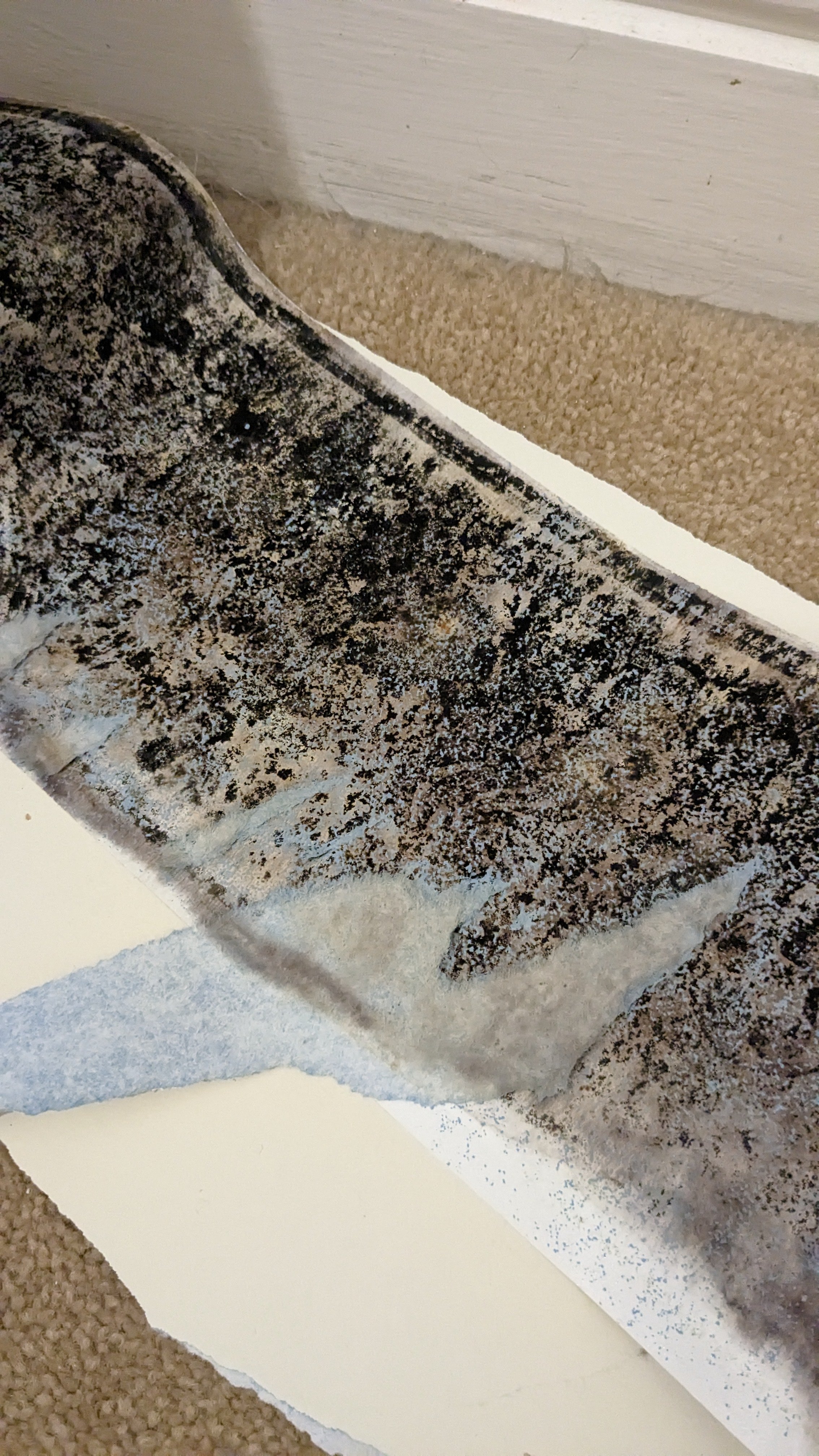

Firstly, traditional carpet underlays are usually made from either rubber (most commonly synthetic rubber), felted wool, or polyurethane (PU) sponge foam, the latter of which we found when lifting the threadbare carpets as part of our renovation. PU foam is made by reacting chemicals (di‐isocyanates) and compounds (polyols), both of which are typically derived from crude oil. It makes for a very soft, lightweight and easy to manouvre product, but it has one very significant environmental problem: it does not biodegrade. Over time, the foam breaks down through wear and friction, as we discovered under our very own carpets. The foam had disintergrated, essentially leaving us with sacks of microplastics to try to safely dispose of.

There are many new types of underlay being manufactured now. Recycled carpet underlay is made from offcuts of carpet that would have traditionally been sent to landfill, or for incineration. Others are made from wool, cork (which we did consider) or blends of both natural and recycled synthetic fibres. I even found one made in the UK from recycled tyres! We let our soundproofing and insulation (TOG rating) requirements guide us, as well as where the product was manufactured and if we could support a local business.

The majority of our carpets manufactured today are made up of synthetic fibres. Most commonly, these are nylon, polypropolene or polyester. And there’s a very good reason for that. They’re easy to clean, are resistant to fading and abrasion, are easy to dye - and are cheap to make. (Thanks fossil fuels.) They are also not biodegradable. There have been so many reports about microplastics being found in human beings - even in the both the maternal and fetal sides of placentas. As these microplastics float in the air, we can inhale or ingest them, and are shed from all stages of a plastic fibre’s lifecycle. We wish to reduce as much contact with synthetic fibres as possible in our home so our choice of carpet was directed towards natural fibres.

Sisal, seagrass, coir, jute and wool are all natural fibres that can be made into floor coverings. Sisal comes from a palm-like plant, native to Mexico. Seagrass is - as the name suggests - a flowering plant grown in the sea. Coir is the natural fibre on the outer shell of a coconut husk and Jute is made from the fibres of plants in the Corchorus genus grown across South Asia. Wool comes, of course, from the shorn fleece of sheep. Each of these fibres offer their own unique qualities when made into flooring mediums, alongside their own carbon footprints based on their manufacture and location of origin.

From my daughter’s bedroom window, we look out directly onto fields of livestock. They alternate between cattle and sheep, but sheep are the mainstay of the view. This was one of the selling points of the house, for us. Those funny, fluffy clouds grazing their way across the crest of the hill, battling all the elements the English weather throws at them. Suffice to say, we witness the durability of wool almost everyday. So a 100% British wool carpet was for us.

Wool’s natural properties means it’s harder to compress the pile, therefore giving longevity of appearance. It can repel dirt and some water and is naturally fire retardant. Wool is also naturally stain resistant - my biggest concern (that, and moths) but we have been given an excellent piece of advice for (inevitably) when we have a spill to clean up. Do not spray or pour your cleaning product onto the carpet.**** Wet the cloth instead. Spraying directly onto the carpet will only push the stain further into the pile, making it much more difficult to remove. Which makes sense when you say it out loud, but in the despair of cleaning up unimaginables from a carpet at 3am with a sick child, isn’t something I’ve practiced before!

Price and value

With everything I’ve shared here, there is a price to consider. I wish I could say I’m entirely immune to the desire of ‘having it now’; I have been as exposed to impulse purchasing and accessibile buying as most of us in Britain. This is what mainstream culture has become - a quick swipe and a day later that lamp/dress/macrame toy storage is at your door. It now feels countercultural to say: I can wait. It takes practice. It takes willpower. I guess you could say there’s an element of the long game involved, too. We had to wait and save but as I said at the beginning of this article, a green home is important to us, so this is where we choose to invest. These two bedrooms took us eight months to complete. We did all the research and a lot of the graft ourselves to keep costs down so we could spend our budget on quality, sustainable materials. The price we paid is weighed against the long term value, a huge proportion of which is not monetary. Being able to share my home with friends and loved ones brings me so much joy. Knowing it is a green, healthy place to be adds to this too. And as we all know, joy is priceless.

References

*Source: Heritage House heritage-house.org

**Source: Mike Wye mikewye.co.uk

***Source: The Forest Stewardship Council fsc.org/en/about-us

**** Source: British Wool shop.britishwool.org.uk

LIKE WHAT YOU’VE READ? I’D BE VERY GRATEFUL IF YOU COULD BUY ME A COFFEE.

My writing here is always free to read. If you’d like to support my stories and help me with the costs in generating its content, you can buy me a coffee. All donations are used to pay for the hosting of the site and my time spent writing.